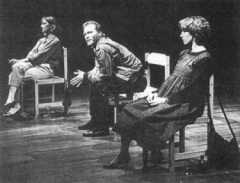

STILL LIFE examines the effects of the Vietnam

War on middle America. In the play, three people -- Mark,

a veteran; Cheryl, his wife; and Nadine, a friend -- sit

on chairs and make statements to the audience about their

own lives and relationships. There is almost no

interchange between them.

STILL LIFE examines the effects of the Vietnam

War on middle America. In the play, three people -- Mark,

a veteran; Cheryl, his wife; and Nadine, a friend -- sit

on chairs and make statements to the audience about their

own lives and relationships. There is almost no

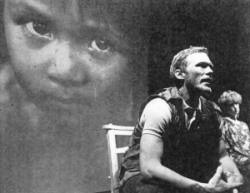

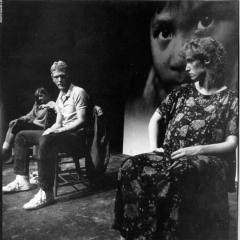

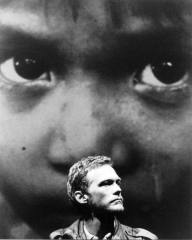

interchange between them. Ten years after Vietnam, Mark is haunted by one

atrocity, the nature of which is not revealed until this

play's closing minutes. One of his obsessions is to show

photos he took in the battle areas of his friends (some

now dead, including his best buddy), of Vietnamese

children and of other victims of war. The pictures are

projected on a screen behind his chair.

Ten years after Vietnam, Mark is haunted by one

atrocity, the nature of which is not revealed until this

play's closing minutes. One of his obsessions is to show

photos he took in the battle areas of his friends (some

now dead, including his best buddy), of Vietnamese

children and of other victims of war. The pictures are

projected on a screen behind his chair.Mark's wife, Cheryl, has moved on from her days of pot and flower-power and now longs for security and a nice home for her son and yet-unborn child. Though victimized by her husband's violent tendencies, she is more frightened of being alone for the rest of her life. She is revived by the love of their child, and the prospect of a second. When Cheryl married Mark she was a sexual innocent, but now her incomprehension of her husband has become disappointment. "There was a time when a man would confess to me 'I'm a jerk' at a private moment, and I would smile sweetly and try to comfort him. Now I believe him."

Nadine, soon revealed to be Mark's mistress, is

an older woman with an acid wit who is finding her veneer

of cynicism cracking up. She is a woman who has managed

to survive the horrors of a marriage break-up and

alcoholism, an independent feminist with a belief that

through understanding we can "come out on the other

side." At last finding herself, she defines

sophistication as "the inability to be surprised by

anything." She understands Mark and sees him as an

artistic individual who is far better for her than the

drunken husband she has divorced. Yet always under the

cheerful surface she is a compulsive worrier, living and

working for her children.

Nadine, soon revealed to be Mark's mistress, is

an older woman with an acid wit who is finding her veneer

of cynicism cracking up. She is a woman who has managed

to survive the horrors of a marriage break-up and

alcoholism, an independent feminist with a belief that

through understanding we can "come out on the other

side." At last finding herself, she defines

sophistication as "the inability to be surprised by

anything." She understands Mark and sees him as an

artistic individual who is far better for her than the

drunken husband she has divorced. Yet always under the

cheerful surface she is a compulsive worrier, living and

working for her children. Mark is lost. A society which asked him to

murder in its name, now rejects him. As one of the women

says, "Men brought the war back home and no one

wanted to look at it." Mark finds it impossible to

adjust. On first meeting his mother, he is scolded for

drinking too much coffee. His wife wants him to be a

provider, to get a job to pay for ice-cream and pop for

the their kids. He misses his gun and takes pictures of

his naked wife then mutilates them. Mark brings himself

to admit that killing was the "best sex of his

life," an "orgasm of glory."

Mark is lost. A society which asked him to

murder in its name, now rejects him. As one of the women

says, "Men brought the war back home and no one

wanted to look at it." Mark finds it impossible to

adjust. On first meeting his mother, he is scolded for

drinking too much coffee. His wife wants him to be a

provider, to get a job to pay for ice-cream and pop for

the their kids. He misses his gun and takes pictures of

his naked wife then mutilates them. Mark brings himself

to admit that killing was the "best sex of his

life," an "orgasm of glory." During the plays final moments, Mark confesses

his guilt of having coldbloodedly slaughtering a family

of five in Vietnam, including two children whose lives he

fantasizes will only be paid for with the life of his own

unborn son. Mark is so scary-screwy that he could do the

job himself, and will probably try.

During the plays final moments, Mark confesses

his guilt of having coldbloodedly slaughtering a family

of five in Vietnam, including two children whose lives he

fantasizes will only be paid for with the life of his own

unborn son. Mark is so scary-screwy that he could do the

job himself, and will probably try.The play explores these problems and asks the questions but can give no answers. "The problem now," as Nadine says, "is knowing what to do with what we know." It is a powerful examination, if ultimately depressing, and, at the end, applause seemed a totally inadequate response in appreciation for what had been explained. Synopsized from reviews by John Fowler for Glasgow Herald and Bryan Christie for The Scotsman, Joyce McMillan for The Guardian, Milton Shulman for Standard, Martin Hoyle for Financial Times

"James Morrison conveyed such a frightening sense of violent passions and guilts barely kept in check.... James Morrison's Mark is a mesmerizing piece of theatre work, whose power lies in the way all emotion is checked and suppressed, while he manages to suggest a fury about to be unlashed." Nichola s de Jongh for The Guardian

"Sitting four-square and clean-cut, James Morrison endows this decent-looking young man with a coiled tension." Martin Hoyle

"For more than an hour and a half three seated characters flawlessly played by James Morrison, Deborah Carlisle and Susan Barnes expose their deepest feelings. I found the experience so moving that I could barely talk about it." John Fowler

"James Morrison's delicate balancing act poised between these two as he juggles with his sanity should not be underestimated." Suzie Mackenzie for Time Out

"James Morrison presents a picture of a tortured and uncomprehending conscience, like a wounded tiger." John Peter for Sunday Times

Awards: STILL LIFE won the Fringe First Award for production.