|

|

| To Lobby | To Playlist |

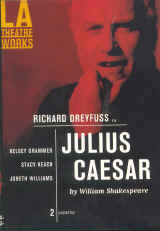

In 1995 the L.A. Theatre Works, with the BBC, co-produced a radio play of

JULIUS CAESAR. In the radio version of Shakespeare’s JULIUS CAESAR, James Morrison played Titinius (a friend to Brutus and Cassius) and The Cobbler. The action begins in February, 44 BC Julius Caesar has just reentered Rome in triumph

after a victory in Spain over the sons of his old enemy, Pompey the Great. A spontaneous

celebration is interrupted and broken up by Flavius and Marullus, two political enemies of

Caesar.

The action begins in February, 44 BC Julius Caesar has just reentered Rome in triumph

after a victory in Spain over the sons of his old enemy, Pompey the Great. A spontaneous

celebration is interrupted and broken up by Flavius and Marullus, two political enemies of

Caesar.